| Death of a Humanist: The Manuel Azaña Story – Part 1 Posted: 07 Nov 2010 12:49 PM PST

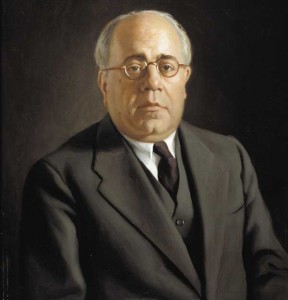

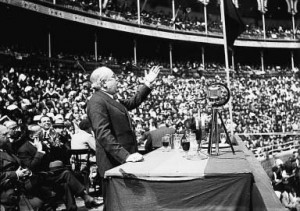

The future President of Spain was born outside of Madrid in 1880. After losing his parents at an early age, Azaña was packed off to be educated by the monks of the Escorial. He detested them. As an adult, he wrote a book called The Garden of the Monks about the anti-intellectual discipline he experienced there. "We learned to refute Kant with five points, and Hegel, and Comte, and so many more. We used to oppose the erroneous assaults with good objections: (1) It is contrary to the teachings of the Church; (2) it leads straight to pantheism; and (3) other puncture-proof reasons." Reducing the supernatural to a series of canned platitudes turned him off: "I have dreamed of destroying all this world," he wrote. He launched his career as a writer by mocking the Church's obsession with relics in a short story about the medieval Spanish hero El Cid. Bones said to be those of El Cid are examined by a doctor and determined to be those of a horse; the archbishop, unconvinced, concludes instead that El Cid must have been a giant. Azaña didn't hate Catholics – he married one, and he and his devout wife respected the other's views throughout their years together. As his writing turned more toward politics, though, he found religion contrary to the necessary virtues of a responsible citizenry: "Pure faith is unsociable; it is not useful in the republic, whose sovereignty it neither strengthens nor defends." Catholicism, in which people owe a loyalty to the Pope superseding what they owe the state, was especially problematic. Azaña's Spain was overwhelmingly Catholic, a fact that can be traced back to the Inquisition established in the 15th century. Though the Inquisition's original purpose was to crack down on Spain's Jews, it proved ideally suited for crushing the outbreak of the Protestant Reformation as well. Hundreds of thousands passed through its torture chambers; as a result, the weakening of the political power of the Catholic Church that occurred in places like England and Germany never happened in Spain. By the dawn of the 19th century the Spanish Church remained every bit as overbearing as it had been 500 years earlier. This left Spain so out of step with the rest of Europe – and so economically backwards – that a low-level armed conflict between Catholics and humanists persisted through most of the 19th century. Meanwhile, Spain continued to stagnate, ultimately losing the last of its overseas possessions to America in 1898. By 1931, the jig was up; the king decided to abdicate, and Spain belatedly joined the rest of Europe in allowing its people to decide how they wished to be governed. The people's overwhelming choice, at the first elections in 1931, was to end the tyranny of the Catholic Church. A coalition led by Manuel Azaña's Republican Action Party swept to power, committed to ending taxpayer subsidies for the Church and breaking the Church's stranglehold on education. Azaña became Prime Minister, and the principal drafter of a new constitution for the new Republic. The constitution Azaña helped produce pointedly refused to recognize Catholicism as the official religion of the state. On the contrary, it infuriated the Church by its explicit toleration of all varieties of religious belief. Control over marriage, cemeteries, and education was transferred from the Church to the civil government, and Church doctrine was further violated by allowing women full rights of citizenship, including the right to divorce. As Azaña put it on the floor of the Cortes: "Spain has ceased to be Catholic." Only five years earlier, the Church had been strong enough to induce the government to imprison a woman for saying that the Virgin Mary bore other children after the birth of Jesus. Those days were over – at least for a while. The Church did not take Azaña's victory lying down. Only two weeks after the 1931 election, the Catholic primate was already condemning the triumph of "the enemies of the Kingdom of Jesus Christ." The Catholic press began trumpeting the success of the Fascists in Italy and the Nazis in Germany as models for Spain.

When the next elections were held in February, 1936, the humanist side reunited. Once again it scored a decisive victory, despite the Church's circulation of a catechism declaring it to be a mortal sin to vote for any candidate who supported freedom of religion, the press, or education. After this defeat, the Catholic side shrewdly gave up on the ballot box. Left to their own devices, Spaniards would never support continued control by God experts. A few months later General Francisco Franco, the recently demoted Army chief of staff, launched an armed rebellion against the people's choice. Franco claimed to be fighting against Communism; in fact, Azaña had excluded all Communists and even Socialists from his government, even though they had contributed to his coalition's success. Ironically, Azaña had devoted much of his energy during his first term in office to modernizing and strengthening the army, and that new-found efficiency was now being used against him. With most of the army on his side, Franco could have swept into power quickly. But speed was not Franco's intent. He sought not a coup, but a permanent revolution, in which the forces of humanism would be crippled beyond hope of recovery. As he wrote to a friendly diplomat:

One of Franco's colleagues, General Mola, spoke of the important role terrorism must play in the Catholic campaign: "It is necessary to spread terror. We have to create the impression of mastery, eliminating without scruples or hesitation all those who do not think as we do. There can be no cowardice. If we vacillate one moment and fail to proceed with the greatest determination, we will not win." General Queipo de Llano spread his own brand of terrorism on radio broadcasts: "Our brave Legionaries … have shown the Red cowards what it means to be a man. And, incidentally, the wives of the Reds, too. These Communist and Anarchist women, after all, have made themselves fair game by their doctrine of free love. And now they have at least made the acquaintance of real men, and not milksops of militiamen. Kicking their legs about and struggling won't save them." Next week: How Azaña tried and failed to save Spain and democracy at the same time. No related posts. |

| You are subscribed to email updates from Secular News Daily To stop receiving these emails, you may unsubscribe now. | Email delivery powered by Google |

| Google Inc., 20 West Kinzie, Chicago IL USA 60610 | |

No comments:

Post a Comment